Refugees

We live in one of the greatest periods of history, a time of unprecedented connectivity, knowledge, and innovation. From Kenya, we can connect instantly to friends and family anywhere on the planet. Though we are half a world away, we could be back in Atlanta in 24 hours. We care for the neediest African children with equipment from Asia and a team of doctors from Kenya, America, and Australia. It is an amazing world, full of incredible opportunities.

But connectivity has its other sides. In Paris, some 200 people were killed in coordinated terror attacks, and thanks to overwhelming connectivity the world is rightly shocked and scared. A year ago, friends and family feared for our safety due to attacks in Kenya. Now fears rage in Europe and once again in America. The temptation is to think that the world is collapsing, that life as we know it is threatened. In reality we live in one of the most peaceful times of human history, the world is not actually falling apart. But it does not feel like that.

So how do we react? What should solidarité look like?

Luther drew a division between the two kingdoms – church and state – that I feel is very significant here. The role of government and leaders is to protect citizens and to preserve and improve quality of life. In many ways it is a leader’s job to feel the full fear of terrorism. While I may not agree, I certainly am not surprised that the reaction is to block refugees and immigrants – they could be dangerous. They could pose a threat to the state.

But what should the response of the church and Christians be to the some 3 million Syrian refugees?

My thoughts are influenced strongly by several sources – first, a series of photos and stories by Humans of New York about a Syrian refugee

This is Muhammad, who I first met last year in Iraqi Kurdistan. At the time, he had just fled the war in Syria and was working as a clerk at my hotel. When war broke out, he’d been studying English Literature at the University of Damascus, so his English was nearly perfect. He agreed to work as my interpreter and we spent several days interviewing refugees who were fleeing the advance of ISIS. As is evident from the quote below, I left Muhammad with the expectation that he’d soon be travelling to the United Kingdom with fake papers. I am retelling the story because I have just now reconnected with Muhammad. He will be working again as my interpreter for the next ten days. But the story he told me of what happened since we last met is tragic.

“The fighting got very bad. When I left Syria to come here, I only had $50. I was almost out of money when I got here. I met a man on the street, who took me home, and gave me food and a place to stay. But I felt so ashamed to be in his home that I spent 11 hours a day looking for jobs, and only came back to sleep. I finally found a job at a hotel. They worked me 12 hours a day, for 7 days a week. They gave me $400 a month. Now I found a new hotel now that is much better. I work 12 hours per day for $600 a month, and I get one day off. In all my free hours, I work at a school as an English teacher. I work 18 hours per day, every day. And I have not spent any of it. I have not bought even a single T-shirt. I’ve saved 13,000 Euro, which is how much I need to buy fake papers. There is a man I know who can get me to Europe for 13,000. I’m leaving next week. I’m going once more to Syria to say goodbye to my family, then I’m going to leave all this behind. I’m going to try to forget it all. And I’m going to finish my education.”

(August 2014 : Erbil, Iraq)

“Before leaving for Europe, I went back to Syria to see my family once more. I slept in my uncle’s barn the entire time I was there, because every day the police were knocking on my father’s door. Eventually my father told me: ‘If you stay any longer, they will find you and they will kill you.’ So I contacted a smuggler and made my way to Istanbul. I was just about to leave for Europe when I received a call from my sister. She told me that my father had been very badly beaten by police, and unless I sent 5,000 Euro for an operation, he would die. That was my money to get to Europe. But what could I do? I had no choice. Then two weeks later she called with even worse news. My brother had been killed by ISIS while he was working in an oil field. They found our address on his ID card, and they sent his head to our house, with a message: ‘Kurdish people aren’t Muslims.’ My youngest sister found my brother’s head. This was one year ago. She has not spoken a single word since.”

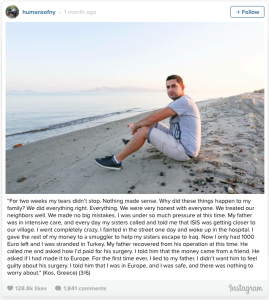

“For two weeks my tears didn’t stop. Nothing made sense. Why did these things happen to my family? We did everything right. Everything. We were very honest with everyone. We treated our neighbors well. We made no big mistakes. I was under so much pressure at this time. My father was in intensive care, and every day my sisters called and told me that ISIS was getting closer to our village. I went completely crazy. I fainted in the street one day and woke up in the hospital. I gave the rest of my money to a smuggler to help my sisters escape to Iraq. Now I only had 1000 Euro left and I was stranded in Turkey. My father recovered from his operation at this time. He called me and asked how I’d paid for his surgery. I told him that the money came from a friend. He asked if I had made it to Europe. For the first time ever, I lied to my father. I didn’t want him to feel guilty about his surgery. I told him that I was in Europe, and I was safe, and there was nothing to worry about.”

“After I told my father that I’d made it to Europe, I wanted nothing more than to turn that lie into the truth. I found a smuggler and told him my story. He acted like he cared very much and wanted to help me. He told me that for 1000 Euros, he could get me to a Greek Island. He said: ‘I’m not like the other smugglers. I fear God. I have children of my own. Nothing bad will happen to you.’ I trusted this man. One night he called me and told me to meet him at a garage. He put me in the back of a van with twenty other people. There were tanks of gasoline back there, and we couldn’t breath. People started to scream and vomit. The smuggler pulled out a gun, pointed it at us, and said: ‘If you don’t shut up, I will kill you.’ He took us to a beach, and while he prepared the boat, his partner kept the gun pointed at us. The boat was made of plastic and was only three meters long. When we got on it, everyone panicked and the boat started to sink. Thirteen of the people were too scared to go. But the smuggler said that if we changed our minds, he would keep the money, so seven of us decided to go ahead. The smuggler told us that he would guide us to the island, but after a few hundred meters, he jumped off the boat and swam to shore. He told us to keep going straight. The waves got higher and higher and water began to come in the boat. It was completely black. We could see no land, no lights, only ocean. Then after thirty minutes the motor stopped. I knew we all would die. I was so scared that my thoughts completely stopped. The women started crying because none of them could swim. I lied and told them that I could swim with three people on my back. It started to rain. The boat began to turn in circles. Everyone was so frightened that nobody could speak. But one man kept trying to work on the motor, and after a few minutes it started again. I don’t remember how we reached shore. But I remember I kissed all the earth I could find. I hate the sea now. I hate it so much. I don’t like to swim it. I don’t like to look at it. I hate everything about it.” (Kos, Greece)

“The island we landed on was called Samothrace. We were so thankful to be there. We thought we’d reached safety. We began to walk toward the police station to register as refugees. We even asked a man on the side of the road to call the police for us. I told the other refugees to let me speak for them, since I spoke English. Suddenly two police jeeps came speeding toward us and slammed on the brakes. They acted like we were murderers and they’d been searching for us. They pointed guns at us and screamed: ‘Hands up!’ I told them: ‘Please, we just escaped the war, we are not criminals!’ They said: ‘Shut up, Malaka!’ I will never forget this word: ‘Malaka, Malaka, Malaka.’ It was all they called us. They threw us into prison. Our clothes were wet and we could not stop shivering. We could not sleep. I can still feel this cold in my bones. For three days we had no food or water. I told the police: ‘We don’t need food, but please give us water.’ I begged the commander to let us drink. Again, he said: ‘Shut up, Malaka!’ I will remember this man’s face for the rest of my life. He had a gap in his teeth so he spit on us when he spoke. He chose to watch seven people suffer from thirst for three days while they begged him for water. We were saved when they finally they put us on a boat and sent us to a camp on the mainland. For twelve days we stayed there before walking north. We walked for three weeks. I ate nothing but leaves. Like an animal. We drank from dirty rivers. My legs grew so swollen that I had to take off my shoes. When we reached the border, an Albanian policeman found us and asked if we were refugees. When we told him ‘yes,’ he said that he would help us. He told us to hide in the woods until nightfall. I did not trust this man, but I was too tired to run. When night came, he loaded us all into his car. Then he drove us to his house and let us stay there for one week. He bought us new clothes. He fed us every night. He told me: ‘Do not be ashamed. I have also lived through a war. You are now my family and this is your house too.’”

“After one month, I arrived in Austria. The first day I was there, I walked into a bakery and met a man named Fritz Hummel. He told me that forty years ago he had visited Syria and he’d been treated well. So he gave me clothes, food, everything. He became like a father to me. He took me to the Rotary Club and introduced me to the entire group. He told them my story and asked: ‘How can we help him?’ I found a church, and they gave me a place to live. Right away I committed myself to learning the language. I practiced German for 17 hours a day. I read children’s stories all day long. I watched television. I tried to meet as many Austrians as possible. After seven months, it was time to meet with a judge to determine my status. I could speak so well at this point, that I asked the judge if we could conduct the interview in German. He couldn’t believe it. He was so impressed that I’d already learned German, that he interviewed me for only ten minutes. Then he pointed at my Syrian ID card and said: ‘Muhammad, you will never need this again. You are now an Austrian!’”

At times I feel like I am any one of the people in Muhammad’s story. I am like the Albanian policeman, secretly helping so that neighbors or others in need don’t see. I am like the jailer, looking suffering in the face and ignoring it. I am like Fritz, organizing community support for the needs of the hospital and patients. I am very often like the smuggler – offering only a small, broken vessel and finger in the right direction.

These questions get at the heart of Christianity and at the heart of personal identity. Who am I, and what is my role in the big story unfolding around me?

“What must I do to inherit eternal life?” the man asked Jesus.

“What is written in the Law?” Jesus replied. “How do you read it?”

“Love the Lord your God with all your heart and soul and mind and strength, and love your neighbor as yourself.”

And Jesus said to him, “You have answered correctly; do this, and you will live.” Luke 10:25-28

What does it mean to love God and to love my neighbor? This is not just an abstract question here in Kijabe. There are so many needs and people asking for help. On a regular basis security guards at the hospital ask for scholarships. Doctors ask for help procuring equipment. Patients are unable to pay bills. Families, virtually every family, is crippled by excessive school fees. How do we love them and care for them in ways that are truly appropriate?

One additional factor that comes into play in Kijabe and definitely in the refugee situation is there are both systemic causes and solutions. At times we may be given the opportunity to help someone like Muhammad, or at times we may even be like him and on the receiving end of help. But more common are the in-between times, when we aren’t Samaritans encountering a bleeding man lying by the roadside – when we are just normal people going about normal life. An individual may not be able to do much for a refugee from afar. But a church may be able to do more, and the entire church – the body of Christ – far, far more than that.

Likewise, the needs in Kijabe are simply too vast for Arianna and I to erase on our own. So we pray, and we work, but we also are very fortunate to do so in part of a remarkable system. 100 years of history are on the side of Kijabe Hospital. A reputation of compassion to people of all cultures from east Africa, regardless of tribe or religious background. Patients who travel for hours and days on horrific roads in jam-packed matatus in search of hope. Training programs preparing future Kenyan leaders to love God, love their neighbors, and to be phenomenal health-care workers. Foreign missionaries who have left incomes and family to move to Kenya. Kenyan missionaries who have likewise forsaken salaries and status to serve the needy. We are grateful that our lives have been entwined in a system of love in which solidarité is not an idea or dream, but a reality.

“But if Jesus Christ is truly risen from the dead, Christianity becomes good news for the whole world – news which warms our hearts precisely because it isn’t just about warming hearts. Easter means that in a world where injustice, violence and degradation are endemic, God is not prepared to tolerate such things – and that we will work and plan, with all the energy of God, to implement the victory of Jesus over them all.” N.T. Wright